By: Renee Skudra

On an uncommonly cold and overcast day last year, heavy with the promise of an early frost, I received an email from the Pauli Murray Center for History & Social Justice. It contained a schedule of events at its Durham facility.

On an uncommonly cold and overcast day last year, heavy with the promise of an early frost, I received an email from the Pauli Murray Center for History & Social Justice. It contained a schedule of events at its Durham facility.

I had never heard of Pauli Murray, so that day was a signal and apocryphal one for me as it immediately piqued my interest in Murray (who I later learned was commemorated by a small wood frame building in Durham, the fifth-largest city in North Carolina).

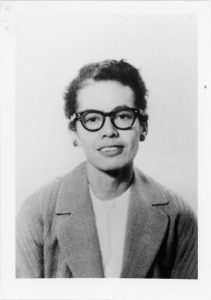

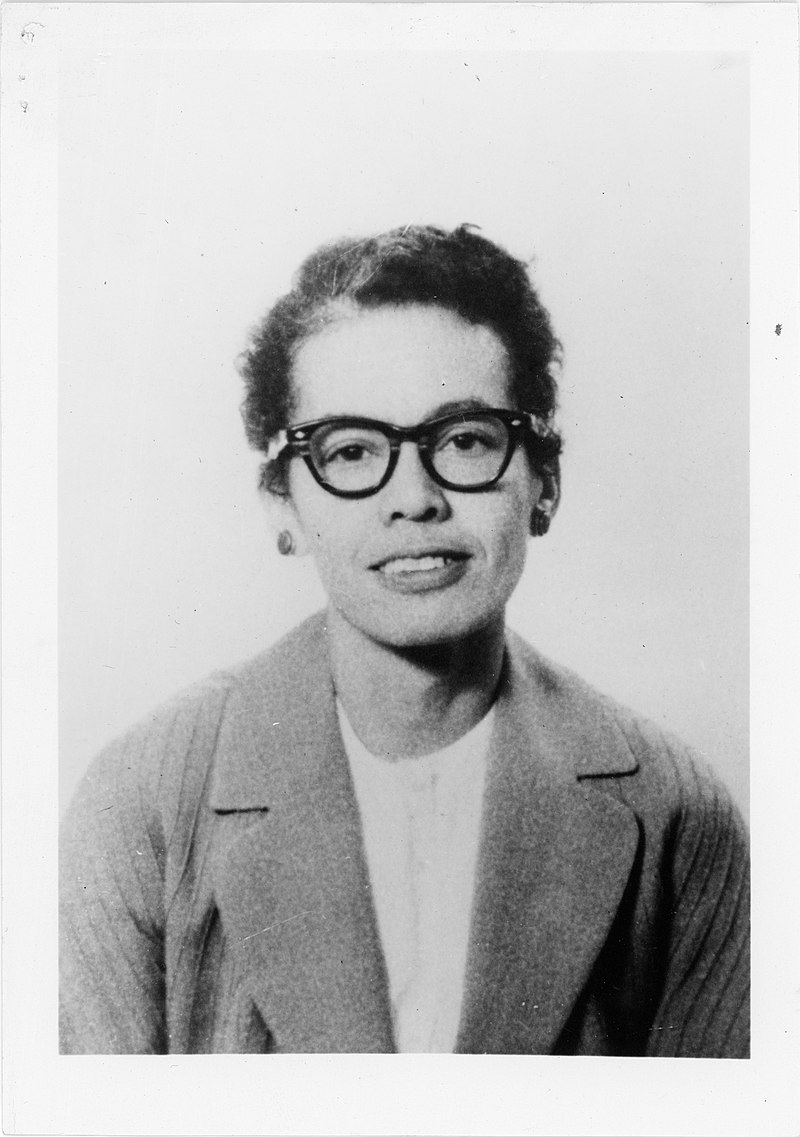

After researching her, I discovered Murray was a multi-racial (Black, white, and American Indian) civil rights attorney and activist, as well as an author.

Much later in life, she became an Episcopal priest who helped write some of the defining civil rights legislation of the 20th century. As her biographer, Rosalind Rosenberg argued — Murray spent her life arguing that race, gender, and economic inequality were interconnected and formulating strategies for battling all types of discrimination.

Gender, like race, isn’t a fixed category. In her words, race and gender discrimination parallel each other and should be considered as “oppressions [that] are interconnected” (Rosenberg, “Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray”). Her work influenced the civil rights movement and expanded legal protection for gender equality, the latter a particularly significant issue since Murray herself had believed from childhood that she was male, and lived with the feeling of being “in-between.”

Murray was born on November 20, 1910 in Baltimore. The granddaughter of a slave, she was adopted at three years old by her aunt Pauline, a teacher, after Pauli’s parents died of natural causes.

Growing up in Durham, she spent her childhood surrounded by aunts and grandparents who valued learning. Pauline apparently accepted her as a “tomboy” who chose to exclusively wear “boy’s clothes,” and later as an adolescent, declared she would not attend a segregated college.

It seemed that Murray, from a young age, recognized that American life was characterized by race being “the atmosphere one breathed from day to day, the pervasive irritant” (Dorrien, “Race, Gender, Exclusion, and Divine Discontent: Pauli Murray and the Intersections of Liberation and Reconciliation”).

As an act of defiance, she enrolled at the age of eighteen at the all-female Hunter College in New York City a discernible woman of color. Once there, she became aware of her attraction to women. She struggled with gender identity and sexuality in the 1930s, a battle which continued throughout her life. She kept her hair short and didn’t wear makeup.

After receiving her degree, she worked a series of jobs, one of which was a labor activist. In 1938, she attempted to enroll in graduate school at the all-white University of North Carolina. She was rejected because of her race, an irony not lost on her since she also had white ancestry and her Caucasian great-grandfather had been a trustee of the school.

The sting of academic rejection still fresh in 1940, Murray fought for equality. That year in Virginia, she refused to sit in the back of a bus and was jailed for violating segregation laws. She subsequently enrolled at Howard University (a Black law school) where she became the valedictorian and only female graduate in the Class of 1944. At Howard, she was an impassioned and obdurately hardworking student who was viewed with promise.

In one of her important law school papers, she noted the psychological harm that segregated schooling inflicted on the well-being of Black children, and she explained a strategy in which segregation might be overthrown as a violation of the 13th and 14th Amendments. Ten years later, NAACP counsel Thurgood Marshall and his legal team used it to prepare for the famous 1954 Brown v. The Board of Education case. The ideas that Murray articulated in that paper eventually found favor: The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

There were, however, other bumps in the road. Upon applying for graduate study in sociology at Harvard University, she was delivered a crushing blow: rejected on account of her sex. Additionally, medical problems plagued her, including hyperthyroidism and constant fatigue. Her life was fraught with struggles.

Privately identifying as male, she sought hormone therapy in the late 1930s and 1940s, but doctors did not consider her a viable candidate. Today, she would probably identify as transgender, but no social movement existed to support that identity during her lifetime. She was forced to exist in a netherworld, painfully aware of a disconnect between her biological female identity and the male identity she felt was her actual birthright.

While she moved from job to job, not staying with any one employer for more than two or three years, she found solace in the world of academia. In 1945, she went on to earn a master’s of law degree from UC Berkeley’s esteemed Boalt Hall, where she wrote her thesis on employment rights.

There, she challenged the constitutionality (under the 13th Amendment) of private discrimination in the sale or rental of housing. In 1968, the Supreme Court accepted her reasoning in the case of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer, Co., holding that such discrimination was among the “badges and incidents of slavery” (William M. Carter, “Race, Rights and the Thirteenth Amendment: Defining the Badges and Incidents of Slavery”).

In a second master’s thesis, she discussed the possibility of using federal legislation to protect Black people from employment discrimination. Her argument foreshadowed the congressional action twenty years later through the vehicle of Title VII.

In 1947, she was admitted to the New York State Bar and began practicing law in Manhattan. In 1951, she wrote “States Laws on Race and Color” which U.S. Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall credited for its value to civil rights lawyers.

In 1956, she was hired by an elite New York law firm, where for many years she was the only attorney recognized as female. While there, she met Rene Barlow, the firm’s office manager. Although they never lived together, their relationship lasted 17 years until Barlow’s death. Barlow served as an emotional mainstay and anchor, seeing Murray through yet another academic triumph: the receipt of her doctor of juridical science (J.S.D.) at Yale’s law school.

In 1964, she coauthored an important article called “Jane Crow & the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII.” Everything societally important seemed to engage her attention.

In 1966, Murray was one of 28 founders of the National Organization for Women (NOW). She found time to work for the ACLU on a landmark Alabama case overturning a ban that didn’t allow women to serve on juries.

She was appointed by President John F. Kennedy to the Presidential Commission on Civil and Political Rights, and was listed by Ruth Bader Ginsburg as a co-author in Reed v. Reed, a gender discrimination case.

Her prodigious life was marked by other extraordinary achievements, as well, including the publication of several books. One of them, “Proud Shoes,” was a critically acclaimed account of Murray as a young mixed-race woman growing up in the Jim Crow South.

Another book was her memoir, “Song in a Weary Throat,” which was published posthumously in 1987 and received many accolades. Some have said that this book is among the great civil rights autobiographies of the 20th century.

Additionally, she wrote “Dark Testament and Other Poems.” It was almost as if she could not stop moving, always fighting through her words in some way for the notion that justice must be color-blind as the U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan asserted, though, that proof was not actually in the American pudding.

Following Barlow’s death in 1973, Murray gave up the law and a tenured professorship at Brandeis University to pursue study at the General Theological Seminary.

Four years later, she became the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Invited to deliver a sermon at the Chapel of the Cross in North Carolina, where a female family member had once been baptized, she said, “Deep in my heart I do believe that the American South will lead the way toward the renewal of our moral and spiritual strength and our sense of mission” (Rosenberg, 378).

Murray dedicated her life to effectively championing the rights of all individuals. She played pivotal roles in both the modern civil rights movement and women’s movement. At age 74, having lived a momentous life, she died of pancreatic cancer.

She was a role model for lesbian and transgender people, though she was sadly forced to live a closeted life.

Her words from her poem – “Hope is a song in a weary throat” – are now curved into a residential college at Yale named after her.

Renee Skudra lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with my Civil War historian son and Bichon Frise, Jackson. I trained to be a lawyer but always wanted to be a writer. I love living in the South with its emphasis on history, family, faith, and hospitality and enjoy foreign films, country western music, fast horses, slow dancing, men with dimpled chins, handmade quilts, salsa dancing, and anything dark chocolate.

Renee Skudra lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with my Civil War historian son and Bichon Frise, Jackson. I trained to be a lawyer but always wanted to be a writer. I love living in the South with its emphasis on history, family, faith, and hospitality and enjoy foreign films, country western music, fast horses, slow dancing, men with dimpled chins, handmade quilts, salsa dancing, and anything dark chocolate.

There are no comments

Add yours