In your lifetime, you probably have had, currently have, or will have HPV.

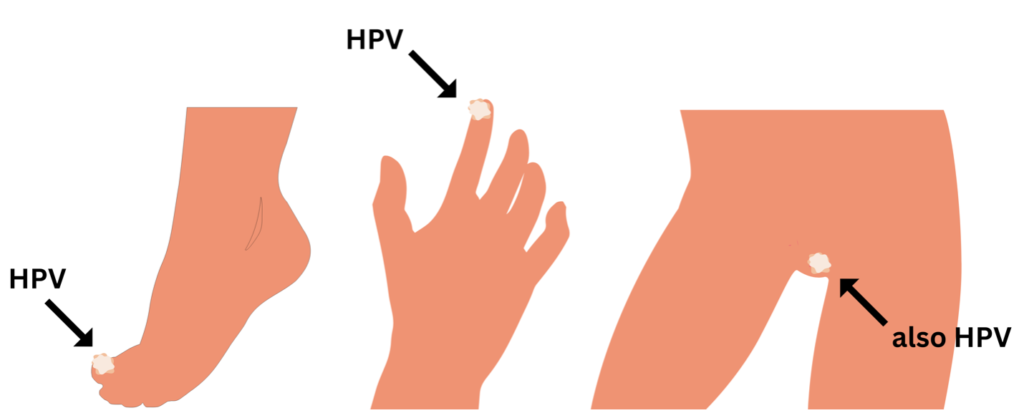

HPV, which stands for Human Papilloma Virus, is an incredibly common group of viruses. HPV describes hundreds of different types of viruses, called strains. Although HPV is commonly thought of as a sexually transmitted infection (STI), these viruses are also responsible for common warts – like the ones you may have seen crop up on your fingers, elbows, or the bottoms of your feet. The sexually transmitted HPVs are so common that every sexually active person will likely contract the virus in their lifetime, unless they are vaccinated.

In short, HPV is a family a viruses – some sexually transmitted, some not – that can cause a range of symptoms in humans, from no symptoms to warts to certain cancers.

HPV is very different than HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), a virus that attacks the immune system and can lead to AIDS, and HSV (Herpes Simplex Virus), a virus that causes cold sores and genital blisters.

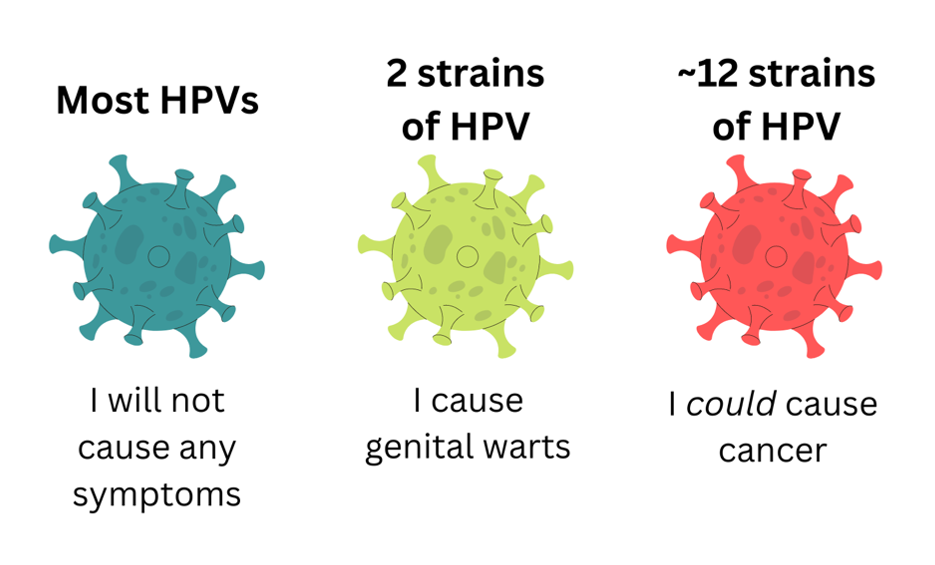

About 40 strains of HPV are known to be passed through sexual contact, such as vaginal, anal, or oral sex. The vast majority of the viruses cause no symptoms at all, in fact, most people will naturally clear the virus within two years of initial infection.

A small proportion of these HPV viruses can cause genital warts or lead to certain cancers. Importantly, the HPV viruses that cause warts ARE NOT known to cause cancers.

Genital warts are not life-threatening. However, they may be itchy, uncomfortable, or make people self-conscious. Fortunately, doctors and nurses can treat warts, as well as provide suggestions for how to keep future sexual partners safe from the same infection.

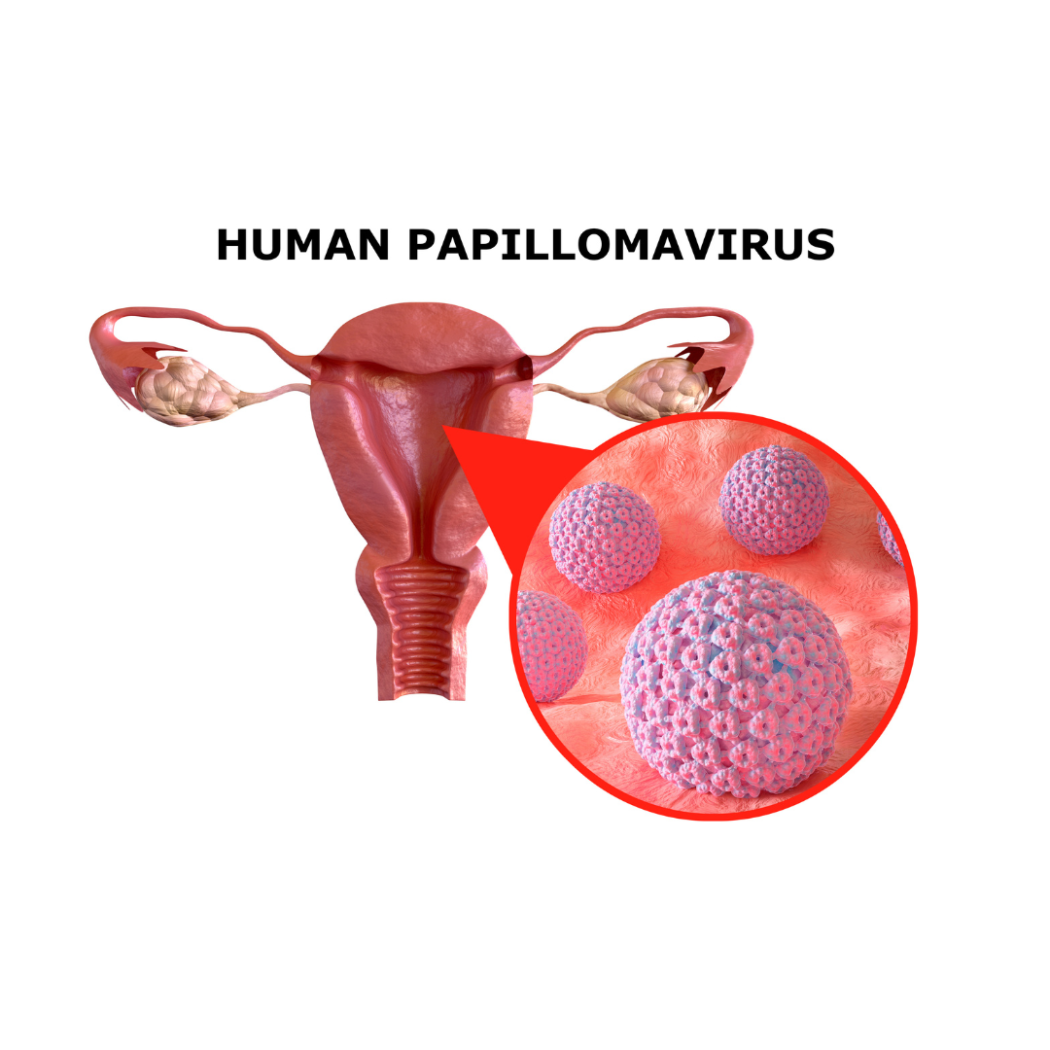

HPV has also been found to cause such as cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, penile, and throat cancers. Although why exactly this happens is still being researched, untreated HPV infection has been shown to significantly increase a person’s risk for these cancers. Every year, HPV is responsible for about 19,400 cancer cases in females and 12,100 in males.

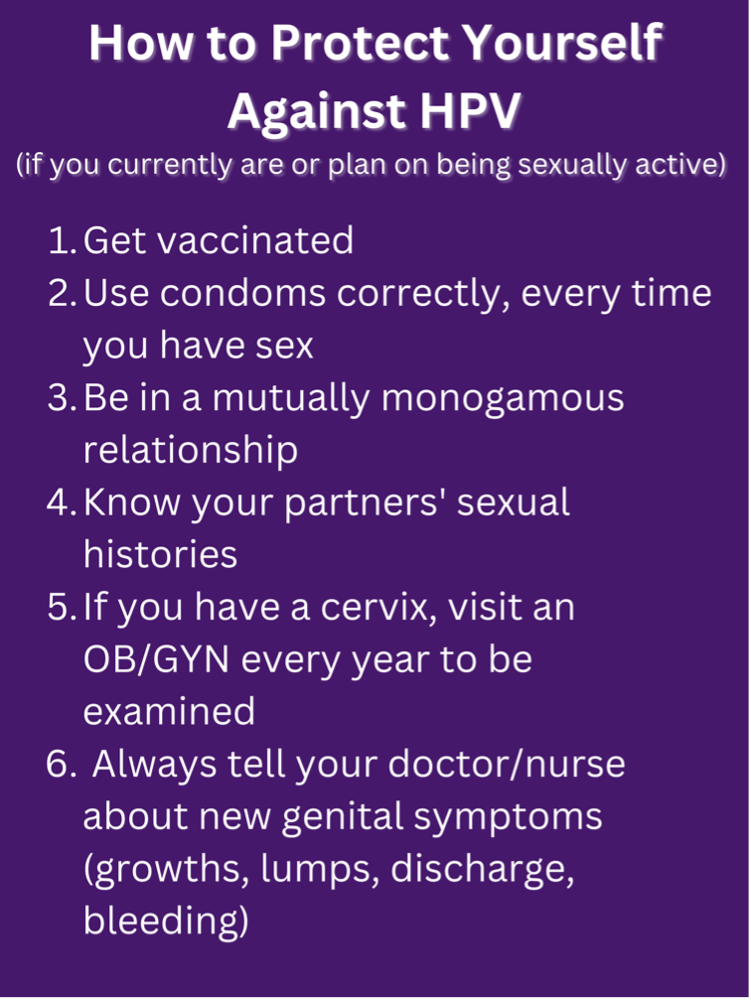

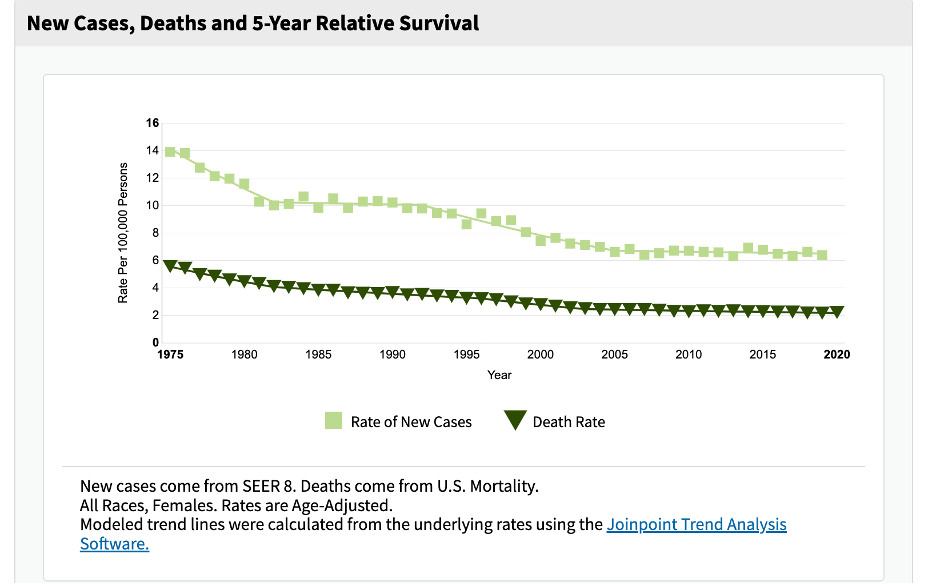

Every year, about 12,000 people will have cervical cancer, and about 4,000 people die of cervical cancer per year. The good news is that cervical cancer takes a very long time to grow – usually years or decades. Annual pelvic exams, as well as pap smears every three or five years, can usually identify cervical precancers, so that patients can receive treatment before it ever becomes a problem.

If you have been going to the OB/GYN for a while, you may remember getting a pap smear every year. However, due to the nature of cervical cancer, the guidance has changed, and every screening every three to five years has been found to be sufficient.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists identifies the reason for the change, saying says: “we now better understand the way cervical cancer develops over time—we know it takes many years to develop—so we’ve expanded the time between screenings. We also now have two screening options to detect cervical cancer, the Pap test and the HPV test.”

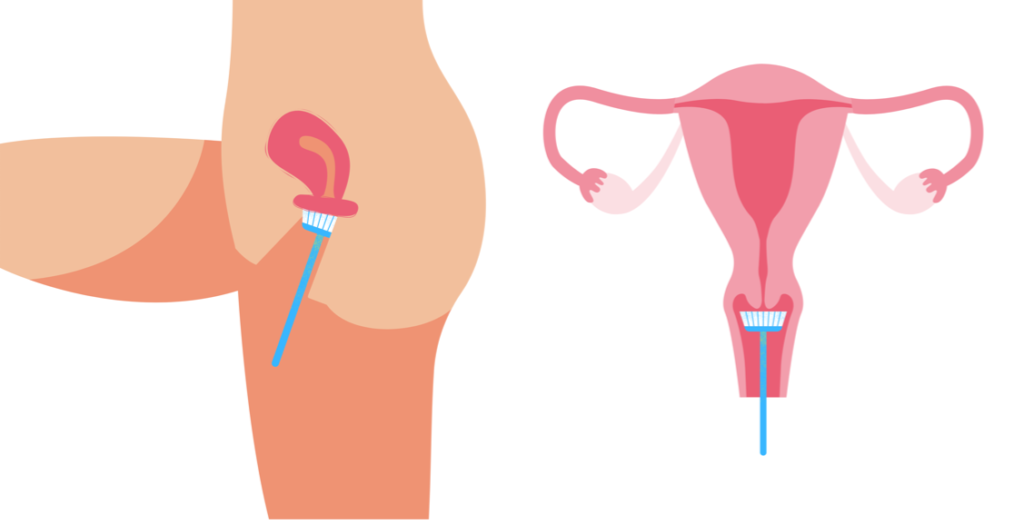

Anatomy of a routine pap smear. A small, flexible brush is inserted into the vagina to collect cells from the outside and inside of the cervix. These cells are then sent to pathology to be examined for signs of precancer or cancer.

In addition, the HPV vaccine, which debuted in 2006, have significantly dropped the number of HPV infections and will likely decrease the amount of cervical cancers. The vaccine, which provides lifelong protection against genital-wart causing HPV strains (6 and 11), as well as the most common cancer-causing strains (16 and 18), as well as some other common strains. These vaccines can be administered as young as 9 years of age, and as old as 45 years of age in some cases. The vaccines are shown to be completely safe and very effective as preventing infection with disease-causing HPVs.

The NIH collected the data below, which shows a significant decrease in the rate of new cervical cancer cases since 1975 (the light green line.) The number of new cases should continue to drop as we approach 2030, 2040, and 2050, when the generation of young people who first received the vaccines in 2006 begin to reach middle age. Because many people of this generation were vaccinated against HPV before starting sexual activity, fewer will contract HPV and fewer will develop cervical cancer.

Make the Most of Your Annual OB/GYN Visit!

Look for a provider who accepts your insurance, then get picky – we all deserve to have a doctor who listens to our concerns, answers questions, uses understandable language, and makes us feel comfortable. If you do not like your OB/GYN, find another!

Prepare before – keep a list of questions or concerns in the weeks leading up to your appointment and have this handy while you meet with your provider.

Conduct monthly breast exams – breasts will naturally feel lumpy and bumpy. Different physiological and environmental factors, like your menstrual cycle, various foods (like chocolate and red wine), and stress, can all make these lumps feel bigger or more tender. However, normal lumps will naturally disappear. If you have a firm, painful, or immobile lump, tell your doctor. Also be aware of other signs of breast cancer, including dimpling, nipple discharge or bleeding, or swelling.

Know your vulva and vagina – you may notice that the inside of the labia majora (the larger folds of skin that cover your vagina) has small, whitish bumps. These are completely normal sebaceous glands that secrete oil and protect your body! Keep track of the natural features of your vulva/vagina (freckles, odors, discharge) so that you can identify if something new or concerning crops up.

Don’t worry about personal grooming – you should never feel pressured to groom your pubic hair or douche for an OB/GYN visit. In fact, these practices can actually put you at higher risk for certain infections!

Arrive early – this will give the nursing staff more time to triage you (take your weight, blood pressure, a urine sample, and get your questions). This can maximize the time you have with your provider!

Ask about what is going to happen – doctors and nurses are trained to explain the procedures they use, but sometimes they forget or choose not to do so. You have every right to opt in and out of exams or ask for certain accommodations, such as a female provider, more lubricant, or a smaller speculum.

Get real about your sexual history – this information is vital to making sure that you receive all the care you need. Tell your doctor about the types of sex you have, your sexual partners, whether you use contraception and/or condoms, and any unprotected sex you have had.

If relevant to you, use this time to talk about acne, menstruation concerns, your mood, or your relationships – OB/GYNs care for so much more than just your reproductive system!

If you are left with unanswered questions, ask to schedule a follow up visit or phone call –Doctors/nurses often have to document in the electronic medical record when an issue was not adequately covered during a visit and an additional appointment is needed. This way, insurance companies will cover the expenses for this supplementary visit. Don’t leave with unanswered questions – set up another appointment with your provider!

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributing to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributing to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

There are no comments

Add yours