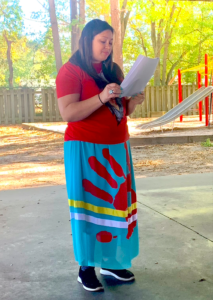

On October 22nd, I attended a family day for the members of Shatter the Silence, a Facebook support group for family members of homicide victims. I was representing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women North Carolina Coalition (MMIW NC), who frequently stands in solidarity with the Shatter the Silence movement given that a large percentage of victims are Native American or Indigenous.

On October 22nd, I attended a family day for the members of Shatter the Silence, a Facebook support group for family members of homicide victims. I was representing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women North Carolina Coalition (MMIW NC), who frequently stands in solidarity with the Shatter the Silence movement given that a large percentage of victims are Native American or Indigenous.

So many cases remain unsolved leaving the loved ones of these victims feeling invisible and silenced. Despite the group having 10,000 members, the loved ones of only 11 victims were able to attend. There was no media present, although they were called. Only one domestic violence agency was represented from Hoke County. A number of the victims are members of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, but there was no tribal leadership in attendance. Only two elected officials, Charles Graham, Representative for House District 47, and County Commissioner Pauline Campbell showed support in person. Although the event was paid for by the county sheriff, there was no law enforcement present to hear the frustrations of broken families.

Some people, who were not there, have demonstrated their commitment to supporting co-homicide victims through their actions, whether it be journalism, podcasts, or targeting harmful legislation, but others benefit from the online image of being associated with the movement and do nothing more. The question is, what is our motivation, and how much are we willing to do to keep the spark in the movements that we care about the most?

Slacktivism, which is defined by the United Nations as supporting causes through minimal effort, is detracting from our ability to fight for sustainable change. Social media is a wonderful tool for spreading awareness about issues, but is deficient in providing measures that result in tangible outcomes. The creation of social media toolkits is beginning to move beyond awareness, but is still limited in creating agency for people to take meaningful action, especially on a local level. The Black Lives Matter movement and the MMIWG2S+ movement are both at risk of growing stagnant under the illusion of online action. Under this influence we often neglect the events happening closest to us, and falter to support movements that have gained national attention.

In 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement took the world by storm after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who killed Trayvon Martin. The movement lost tread when it became a hashtag. In the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd, controversy arose about the use of black squares to promote racial equity on social media.

Posting the black square served as an easy way for people to show solidarity with Black people, but nothing more. Allie Moore, one of my mentors, told me once that “we don’t want allies, we want accomplices.” How many people who posted the black square physically showed up to a protest? How many of them called out a racist family member? Who pulled over on the side of the road and stood by when a Black person was pulled over by the police? Do we continue to check on the families directly impacted? The message of denouncing white supremacy and police brutality has become somewhat lost in social media trends and kitsch fashion statements

Posting the black square served as an easy way for people to show solidarity with Black people, but nothing more. Allie Moore, one of my mentors, told me once that “we don’t want allies, we want accomplices.” How many people who posted the black square physically showed up to a protest? How many of them called out a racist family member? Who pulled over on the side of the road and stood by when a Black person was pulled over by the police? Do we continue to check on the families directly impacted? The message of denouncing white supremacy and police brutality has become somewhat lost in social media trends and kitsch fashion statements

The MMIWG2S+ movement became known as such in Canada around 2015 as Indigenous women activists brought attention to the women lost and murdered on the Highway of Tears. We say that the movement is 500+ years old and the perpetration against Indigenous women was initiated at first contact. The red handprint has become a symbol of the MMIWG2S+ movement. Red can be seen by the spirits, and the handprint over the mouth is symbolic of Indigenous people being silenced. Social media has lit up with beautiful artwork and photos of women in ribbon skirts with the red hand print over the mouth. But similar to the BLM movement, action is lost through likes and shares. People feel that when they share the content, that is the extent of their involvement with the issue.

In Robeson County, it sometimes feels as if we wait for the next murder to feel the pulse. Instead of steadily advancing, we backtrack and decline. We don’t continue to show up for the loved ones of murder victims. We stop checking in on the status of victims’ cases. We are satisfied with performative actions by North Carolina.

A proclamation of a day of recognition is not enough, and the same proclamation language has been used by Governor Cooper’s office since 2019. Tribal leadership often takes little to no action. Wearing red ribbon shirts is not the solution. Using our sovereignty to create prevention programming and support groups is part of the solution.

There have been instances when social media contributed to the passing of legislation on a federal level, such as how social media popularity has contributed to crafting legislation such as the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which has passed the House. The Missing and Murdered Indigneous Women’s Movement has benefitted from the Not Invisible Act and Savannah’s Act. However, federal legislation does not always capture the nuances of issues on a state and local level, meaning that we still have to take action to encourage our state legislature and local politicians to be involved.

There have been instances when social media contributed to the passing of legislation on a federal level, such as how social media popularity has contributed to crafting legislation such as the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which has passed the House. The Missing and Murdered Indigneous Women’s Movement has benefitted from the Not Invisible Act and Savannah’s Act. However, federal legislation does not always capture the nuances of issues on a state and local level, meaning that we still have to take action to encourage our state legislature and local politicians to be involved.

Shatter the Silence is a local movement in Robeson County that has members from all racial backgrounds in the group, all who have stories that fit into national movements for social change. Black Lives Matter, but Marqueise Coleman’s mother still wants the man who killed her son brought to justice. We want justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, but Wendy Jones’s mother has not received much support from tribal leadership or her community.

We have to be more vocal and willing to take actions within our local communities. Creating the world that we want for our children involves taking action beyond a click. The work is more painful when it’s close to home, but we have to push as a labor of revolutionary love.

Aminah is an integrative researcher, activist for Indigenous and Black issues, and advocate fighting violence against women and children. Aminah grew up in Pembroke, North Carolina and is a member of the Lumbee Tribe. Beyond being a Division I track and field athlete in college, Aminah has also channeled her energies into her education having studied Biology at East Carolina University and completing a Masters in Physiology and Biophysics with a concentration in Integrative Medicine from Georgetown University. Her research with Breaths Together for a Change centers blending wisdom traditions, Indigenous epistemology, with Western epistemology to test how mindfulness can reduce racial bias and heal historical trauma. She has served as a Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault victim advocate, a board member for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women NC Coalition, and created Good Medicine Woman LLC to address gaps in knowledge about Indigenous culture. She ran for NC House District 47 in 2022, and is an ECU 40 under 40 Leadership Award recipient.

Aminah is an integrative researcher, activist for Indigenous and Black issues, and advocate fighting violence against women and children. Aminah grew up in Pembroke, North Carolina and is a member of the Lumbee Tribe. Beyond being a Division I track and field athlete in college, Aminah has also channeled her energies into her education having studied Biology at East Carolina University and completing a Masters in Physiology and Biophysics with a concentration in Integrative Medicine from Georgetown University. Her research with Breaths Together for a Change centers blending wisdom traditions, Indigenous epistemology, with Western epistemology to test how mindfulness can reduce racial bias and heal historical trauma. She has served as a Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault victim advocate, a board member for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women NC Coalition, and created Good Medicine Woman LLC to address gaps in knowledge about Indigenous culture. She ran for NC House District 47 in 2022, and is an ECU 40 under 40 Leadership Award recipient.

There are no comments

Add yours