If someone is sexually assaulted, they can choose to complete a rape kit. This kit, collected by a trained health care professional, gathers evidence from the person’s body, such as clothing fibers, hair, skin cells, and bodily fluids. Once completed, a rape kit not only can corroborate a person’s story but also can lead to the identification and/or arrest of the perpetrator.

In the wake of a sexual assault, getting to a hospital and collecting a rape kit may be among the last things a person wants to undergo. However, having a completed rape kit is important if a survivor chooses to press charges against their attacker. It is a sobering reality of our justice system – in order to build a case, every shred of evidence is needed, and time is of the essence. Rape kits need to be collected within 96 hours of the assault or the evidence collected is deemed unusable. So while the hours and days following an assault are critically important to healing, it is also a critical time to begin the legal process of identifying and prosecuting sexual predators.

Because sexual assaults and rapes predominantly happen behind closed doors, many rape cases are colloquially and simplistically defined as “he said, she said” cases, meaning that in the absence of other witnesses, it is one person’s story of what happened against another’s. It is imperative that survivors of sexual assault have every resource possible to collect evidence, strengthen their testimony, and build legal cases against their attacker. Why then are thousands of rape kits left untested in the U.S.?

Sexual violence is common and affects all people, especially young women, trans folks, Native Americans, and people who are developmentally disabled.

Every 68 seconds, someone is sexually assaulted in the U.S. On average, 463,634 people aged 12 and over are sexually assaulted or raped every year. A person of any age can be sexually assaulted; however, those aged 18-34 experience the highest proportion of sexual assaults – 54% of the total.

Although people of all genders experience sexual assault, women are particularly vulnerable. 1 out of every 6 American women has experienced an attempted or completed rape. 82% of all rape survivors who are minors are girls. 90% of all rape survivors who are adults are women. Women aged 18-24 are at the highest risk of all women – they experience sexual violence between 3 and 4 times as much as women in general.[1]

However, contrary to popular belief, cisgender women do not experience the highest rates of sexual violence. In fact, 64% of transgender people have experienced sexual violence, about 3 times more than cisgender women and 6 times more than cisgender men.[2]

Among all races and ethnicities, people identifying as indigenous are at the highest risk of experiencing sexual violence. Of assaults against indigenous people, 41% of assaults are committed by a stranger; 34% by an acquaintance, and 25% by an intimate partner or family member.[3]

A 1995 study estimated that 90% of people who are developmentally disabled and/or neuro-divergent experience sexual abuse during their lives. Some of these survivors are non-verbal, meaning they may have a more challenging time expressing what has happened to them. Predators and abusers look for opportunity and vulnerability in others to commit acts of sexual violence. This decreased risk of accountability puts people who are disabled at a particular risk.[4]

In North Carolina, about 12,000 people report being sexually assaulted every year. 79% percent of sexual assault survivors are women, 13% are men, and 8% are gender diverse or gender non-conforming.

Sexual violence, assault, and rape of all forms is extremely distressing and traumatic, both immediately and long-term. Compared to other Americans, survivors of sexual assault are 3 times more likely to experience depression, 4 times more likely to contemplate suicide, 6 times more likely to suffer from PTSD, 13 times more likely to abuse alcohol, and 26 times more likely to use drugs. In addition, rape survivors are more likely to develop tension and argue with intimate partners, family, and coworkers following an assault.[5]

Deciding to Report

Although the number of reported sexual assaults is already concerningly high, an estimated 60% of all rapes and sexual assaults are never reported to the police.[6]

Choosing not to report a sexual assault is a valid decision. However, without reporting these crimes, abusers may never be held accountable and may go on to perpetrate more sexual violence against others. In addition, after reporting sexual assaults, survivors often are connected to needed resources for healing, such as therapy, support groups, and victim compensation. In this way, reporting a sexual assault can be a beneficial action for a survivor.

According to RAINN (the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), survivors face tremendous stigma, shame, and fear when deciding to report. Among the most common reasons to delay reporting or not report at all are: knowing the abuser, being in a past or current intimate relationship with the abuser, and worrying about not being believed or getting into trouble. All of these reasons are understandable; however, absolutely none of them negate the criminality of sexual assault. No matter who the attacker and survivor are, sexual assault is always a crime and moral violation.

The Reporting Process

After someone is sexually assaulted, they have options on how to move forward. They may choose to:

- not report the assault at all

- obtain a rape kit (also called a sexual assault forensic exam or SAFE) without reporting the assault

- report the assault without obtaining a SAFE

- obtain a SAFE and report the assault

A sexual assault forensic exam can be performed in any hospital by a trained Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner or Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner. During an exam, the health care provider will:[7]

- address injuries that need immediate medical attention

- take a history of the assault, which helps to identify areas of injury or evidence

- perform a full physical, often including internal examinations of the mouth, vagina and/or anus

- Take blood, urine, or swab samples from various spots on the body

- take pictures of injuries

- collect items of clothing

- go through the process of mandatory reporting, if required by state law

*Survivors can decline any part of the SAFE. In addition, no survivor will ever be asked to pay for their own SAFE.

Importantly, survivors can receive a SAFE without reporting the assault to police or identifying themselves as the victim. Per the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, all survivors are entitled to anonymous “Jane Doe rape kits” and can choose to identify themselves later in the legal process if desired.[8] This is an extremely important stipulation – not only does it allow law enforcement to pursue sexual criminals without involving the victim, but it also allows victims to provide needed evidence while taking time to contemplate their desired role in the ensuing legal process.

The Rape Kit Backlog

After experiencing a sexual assault, obtaining a SAFE is an involved, arduous, and possibly retraumatizing experience. Obtaining a SAFE is also an incredibly courageous decision. It requires a survivor to acknowledge the trauma they have just been subjected to, transport themselves to a medical center, submit to invasive questioning and examinations, and begin a dehumanized legal process – all in the hope of eventual justice and healing. In addition, providing a SAFE is a civic service, because a survivor is providing evidence from their own trauma to help law enforcement prosecute sexual criminals.

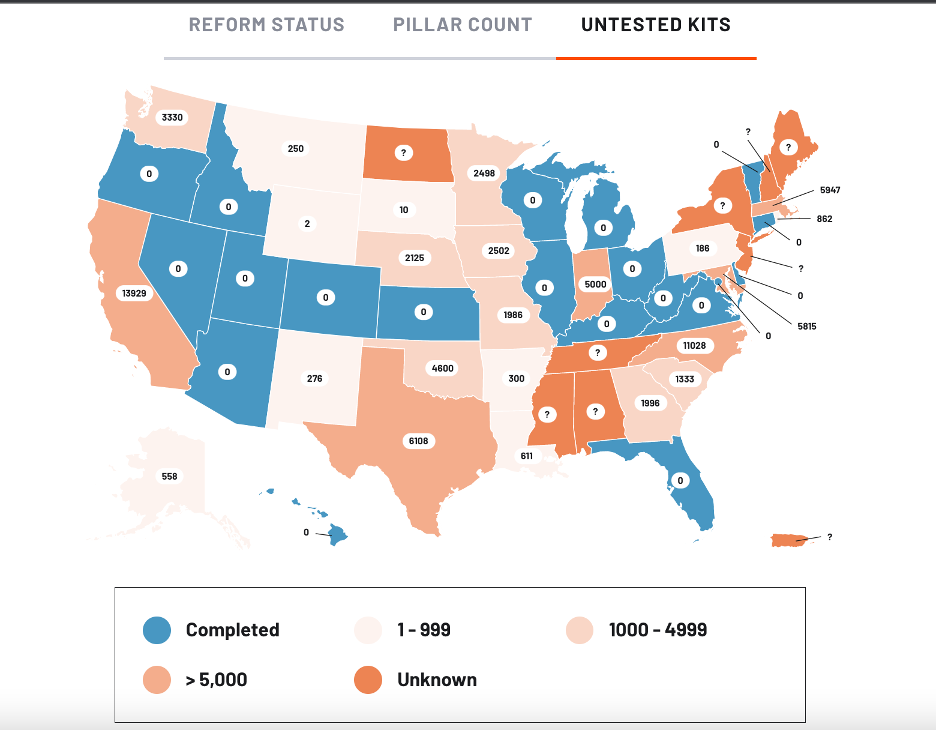

Given the bravery of resolve required of survivors to provide SAFEs, it is unacceptable that there are thousands of untested kits in the U.S. End the Backlog (ETB), a nonprofit dedicated to testing all untested rape kits, provides the map below to visualize these backlogged kits by state:

North Carolina has among the most untested SAFEs – over 11,000. This amount is surpassed only by California, a state with almost four times as many people.

According to ETB, Rape kits become backlogged after they are:[9]

(1) booked into evidence, but law enforcement does not request DNA analysis

(2) left in police storage, hospital, or crisis centers without being sent for testing

(3) sent to a crime lab, but entered into a long queue of kits awaiting testing

So why are these vitally important kits often sequestered into the backs of labs, waiting years to be tested and sometimes never tested at all?

End the Backlog identifies that a lack of knowledge/training in law enforcement contributes to building the backlog. Untrained officers may be inclined to victim-blame based on the circumstances of an assault and thus choose not to submit a SAFE for testing. In addition, some law enforcement officers erroneously believe that SAFE testing is not needed if the identity of the perpetrator is already known, for example, in cases of intimate partner violence.

As End the Backlog describes, rape kit testing has “significant value beyond identifying an unknown suspect. Testing rape kits can link unsolved crimes to a serial offender, confirm a suspect’s contact with a survivor, corroborate a survivor’s account of the attack, and exonerate innocent victims… Testing every rape kit connected to a reported crime ensures that links between crimes will be made, regardless of the relationship between the survivor and the perpetrator.” In other words, testing every rape kit is an essential part in the landscape of justice for sexual assault survivors and accountability for sexual predators.

In addition, a lack of resources often delays the testing of rape kits. It costs, on average, between $1,000 – 1,500 to test a single rape kit. In recent decades, crime labs have also been notoriously overwhelmed due to the demand for DNA evidence in an array of crime scenes, such as homicides and robberies. As a result, survivors may wait months or years to see their kit tested.

Ending North Carolina’s Backlog

In his 2016 campaign, one of Attorney General Josh Stein’s promises was to eliminate North Carolina’s backlog of rape kits, among the worst in the country. Since his term began in 2017, Stein has worked to uphold his promise. Under his administration, North Carolina’s backlog has decreased from over 15,000 untested kits to just over 11,000.

Beginning in 2017, the North Carolina Department of Justice began a statewide inventory of all untested rape kits, uncovering 15,160 untested kits. Largely through grant funding, crime labs in major cities like Charlotte and Durham have been able to shrink this backlog by over 4,000 kits.

Among the most important developments during Stein’s tenure has been the 2019 Survivor Act. Also called the Standing Up for Rape Victims Act, the Survivor Act established legislation to ensure that all future SAFEs are tested in a timely manner. Nowadays, SAFEs must be reported to law enforcement within 24 hours and then transported from police custody to state crime labs within 45 days of receipt. In addition, to shrink the backlog, the Survivor Act delegated $6,000,000 over a 2-year period to testing inventoried SAFEs statewide.[10]

Examining Rape Culture

Although testing each and every rape kit is an important step in establishing justice for sexual assault survivors, a larger issue remains at hand. Why are there thousands of rape kits to begin with? Why do so many people, especially women, experience sexual misconduct, assault, and rape?

If you are a woman, you likely live with a list of safety measures to protect yourself from sexual violence – don’t walk alone at night, make sure someone always knows where you are, carry pepper spray – countless restrictions and requirements to keep your body safe from harm. Women accept the burdensome reality of sexual violence and take endless precautions to avoid being victimized. The onus falls on women to protect themselves from a violent culture created and perpetuated by men.

The Women’s Center of Marshall University defines “Rape Culture” as an “environment in which rape is prevalent and in which sexual violence against women is normalized and excused.” They identify the following examples of “Rape Culture”:

- Blaming the victim (“She asked for it!”)

- Trivializing sexual assault (“Boys will be boys!”)

- Sexually explicit jokes

- Tolerance of sexual harassment

- Inflating false rape report statistics

- Publicly scrutinizing a victim’s dress, mental state, motives, and history

- Gratuitous gendered violence in movies and television

- Defining “manhood” as dominant and sexually aggressive

- Defining “womanhood” as submissive and sexually passive

- Pressure on men to “score”

- Pressure on women to not appear “cold”

- Assuming only promiscuous women get raped

- Assuming that men don’t get raped or that only “weak” men get raped

- Refusing to take rape accusations seriously

- Teaching women to avoid getting raped instead of teaching men not to rape

Marshall University continues, “Rape Culture affects every woman. The rape of one woman is a degradation, terror, and limitation to all women. Most women and girls limit their behavior because of the existence of rape… Men, in general, do not. That’s how rape functions as a powerful means by which the whole female population is held in a subordinate position to the whole male population, even though many men don’t rape, and many women are never victims of rape.”[11]

Rape Culture is additionally problematic because it ignores the reality that rape also affects boys and men. About 1 in 33 American men have experienced an attempted or completed rape,[3] while 1 in 10 men have experienced sexual assault.[4] However, of all demographics, men are the least likely to report sexual violence.[5] It is damaging to assume that all rape victims are women, and that all rape perpetrators are men, because it disregards the boys and men who have experienced sexual violence and are equally deserving of justice and healing.

Although Rape Culture particularly disadvantages girls and women, it affects everyone. Rape Culture lays the foundation for sexual assault to not only happen more frequently, but to be taken less seriously when it does. Historically, women have assumed the burden of Rape Culture by censoring their own actions, behaviors, and appearances in order to stay safe. It’s time for men to share equal responsibility for the culture they have created.

The United Nations Women organization provides this fantastic list for how we can all combat Rape Culture:

1. Create a culture of enthusiastic consent.

Freely given consent is mandatory, every time. Rather than listening for a “no,” make sure there is an active, “yes,” from all involved. Adopt enthusiastic consent in your life and talk about it.

2. Speak out against the root causes.

Rape culture is allowed to continue when we buy into ideas of masculinity that see violence and dominance as “strong” and “male” and when women and girls are less valued.

3. Redefine masculinity.

Take a critical look at what masculinity means to you and how you embody it. Self-reflection, community conversations, and artistic expression are just some of the tools available for men and boys (as well as women and girls) to examine and redefine masculinities with feminist principles.

4. Stop victim-blaming.

Because language is deeply embedded in culture, we may forget that the words and phrases we use each day shape our reality.

Rape-affirming beliefs are embedded in our language: “She was dressed like a slut. She was asking for it,”

It is part of popular song lyrics: “I know you want it.”

It is normalized by objectifying women and calling them names in pop culture and media.

You have the power to choose to leave behind language and lyrics that blame victims, objectify women and excuse sexual harassment. What a woman is wearing, what and how much she had to drink, and where she was at a certain time, is not an invitation to rape her.

5. Have zero tolerance.

Establish policies of zero tolerance for sexual harassment and violence in the spaces in which you live, work, and play. Leaders must be particularly clear that they are committed to upholding a zero-tolerance policy and that it must be practiced every day.

As a starting point, take a look at what you can do to make harassment at work history.

6. Broaden your understanding of rape culture.

Across time and contexts, rape culture takes many forms. It’s important to recognize that rape culture goes beyond the narrow notion of a man assaulting a woman as she walks alone at night.

For instance, rape culture encompasses a wide array of harmful practices that rob women and girls of their autonomy and rights, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation.

7. Take an intersectional approach.

Rape culture affects us all, regardless of gender identity, sexuality, economic status, race, religion or age. Rooting it out means leaving behind restrictive definitions of gender and sexuality that limit a person’s right to define and express themselves.

Certain characteristics such as sexual orientation, disability status or ethnicity, and some contextual factors, increase women’s vulnerability to violence.

8. Know the history of rape culture.

Rape has been used as a weapon of war and oppression throughout history. It has been used to degrade women and their communities and for ethnic cleansing and genocide.

9. Invest in women.

Donate to organizations that empower women, amplify their voices, support survivors, and promote acceptance of all gender identities and sexualities.

10. Listen to survivors.

In the era of #MeToo, #TimesUp, #NiUnaMenos, #BalanceTonPorc, and other online movements, survivors of violence are speaking out more than ever before. Listen to their experiences, read stories of survivors and activists around the globe.

Don’t say, “Why didn’t she leave?”

Do say: “We hear you. We see you. We believe you.”

11. Don’t laugh at rape.

Rape is never a funny punchline. Rape jokes delegitimize sexual violence, making it harder for victims to speak up when their consent is violated.

Humor that normalizes and justifies sexual violence is not acceptable. Call it out.

12. Get involved.

Rape culture is held up by the absence or lack of enforcement of laws addressing violence against women and discriminatory laws on property ownership, marriage, divorce and child custody.

13. End impunity.

To end rape culture, perpetrators must be held accountable. By prosecuting sexual violence cases, we recognize these acts as crimes and send a strong message of zero-tolerance.

Wherever you see pushback against legal consequences for perpetrators, fight for justice and accountability.

14. Be an active bystander.

Violence against women is shockingly common, and we may become witness to non-consensual or violent behavior. Intervening as an active bystander signals to the perpetrator that their behavior is unacceptable and may help someone stay safe.

15. Educate the next generation.

It’s in our hands to inspire the future feminists of the world. Challenge the gender stereotypes and violent ideals that children encounter in the media, on the streets, and at school. Let your children know that your family is a safe space for them to express themselves as they are. Affirm their choices and teach the importance of consent at a young age.

16. Start—or join—the conversation.

Talk to family and friends about how you can work together to end rape culture in your communities.

National Sexual Assault Hotline (available 24 hours)

[1] RAINN

[2] Our Voice NC

[3] RAINN

[4] Our Voice NC

[5] World Health Organization, 2002

[6] U.S. DOJ National Crime Victimization Study 2005

[7] RAINN

[8] RAINN

[9] End the Backlog

[10] NC DOJ Survivor Act Law Fact Sheet

[11] https://www.marshall.edu/wcenter/sexual-assault/rape-culture/

[12] RAINN

[13] U.S. DOJ National Crime Victimization Study 2005

[14] Our Voice NC

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributing to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributing to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

There are no comments

Add yours