This article originally appeared in The Atlantic and has been published with the author’s permission.

To preserve Black history, a 19th-century Philadelphian filled hundreds of scrapbooks with newspaper clippings and other materials. But now underfunding and physical decay are putting archives like this one at risk.

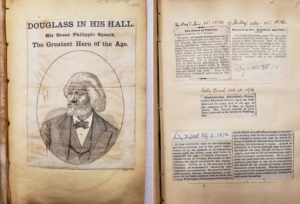

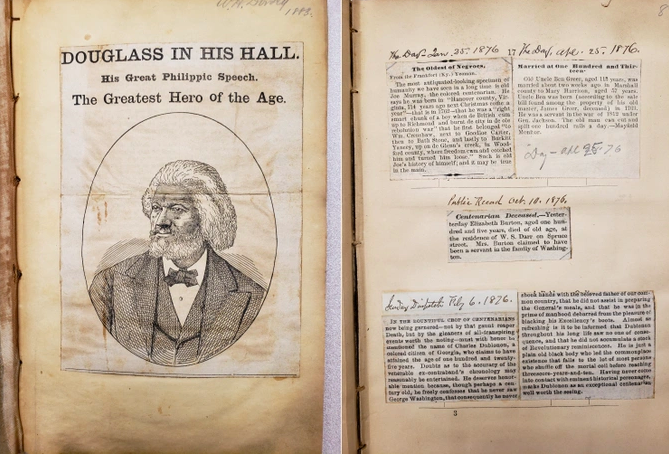

Frederick Douglass was the subject of more than one of William Henry Dorsey’s scrapbooks. (Courtesy of the Penn Libraries)

William Henry Dorsey was an information hoarder. An African American of means who lived in 19th-century Philadelphia, Dorsey suffered from a “malady” that afflicted others of his era: archive fever. He spent much of his long life—he was born in 1837 and died in 1923—clipping newspaper articles and pasting them into one or another of nearly 400 scrapbooks, organized by topic.

Dorsey’s scrapbooks represent a bricolage of one man’s far-ranging interest in African American history and culture. He clipped articles mainly from northern newspapers, Black and white, including some extremely rare publications. The scrapbooks hold articles on Black emigration schemes, fraternal orders, actors, and centenarians who lived through slavery. Dorsey devoted one scrapbook to an 1881 North Carolina convention of Black Republicans, one of many such gatherings at which African Americans envisioned post-emancipation political futures. He devoted another scrapbook to lynchings, and several scrapbooks to Frederick Douglass. Dorsey’s work spans the esoteric and the everyday, and serves as an invaluable record of Reconstruction’s promise and failure, and the nation-changing journey of Black people from chattel to citizens.

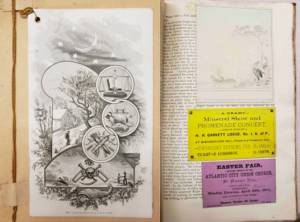

Dorsey made the scrapbooks by hand. As his base material, he often used existing volumes or wallpaper books. He neatly pasted newspaper clippings or printed programs from community events atop the pages, frequently dating these palimpsests in his own hand. He sometimes bound pages together with crimson string that remains bright more than a century later.

In the fall of 1896, the Philadelphia Times published articles about two visits to Dorsey’s “humble dwelling” at 206 Dean Street. The reporter found a collector so consumed by the need to document Black history that he had transformed the top floor of his rowhouse into an “African museum.” Dorsey had amassed a prodigious library concentrating on Black achievement, along with a jumble of eclectica. Walls were hung with engravings, as well as a glass painting of the British Parliament, a mosaic of St. Peter’s Basilica, and paintings by Black artists (of such quality, the reporter remarked, that “one must confess to a feeling of surprise when it is found that a large majority of the excellent oil and water color paintings upon his walls are the work of negroes”). Bookshelves offered a bounty of treasures: a slim volume of Phillis Wheatley’s poems, published in the late 1700s; the chronicles of the abolitionist Ignatius Sancho, a former slave and the first Black citizen known to have cast a vote in Britain; mementos related to onetime Haitian President Faustin Soulouque; and letters by Sojourner Truth. The reporter took particular note of the hundreds of handmade scrapbooks arrayed on Dorsey’s shelves.

And Dorsey explained himself to the newspaper, delivering a passionate and personal mission statement:

It has been my continual aim, as I have journeyed along, to gather every fragment of published matter concerning the colored race. I have spared neither time nor money in prosecuting this hobby—you preserve any data in its original state, you will find it cut out and placed in its proper position. I have not made any history; I have simply collated, and to anyone wishing to write an essay or a volume upon the history or progress of the colored race in this nineteenth century, I have here material that cannot be duplicated elsewhere. My portraits, books and letters are simply priceless, and nothing gives me more pleasure than to show and explain them to anyone feeling sufficient interest in them to visit me.

One such visitor was W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1896, Du Bois moved to Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward to research the book he would later publish as The Philadelphia Negro, his landmark study of urban Black America. Clad in a three-piece suit and top hat, the 28-year-old Du Bois canvassed the district door-to-door with trademark thoroughness, interviewing some 5,000 residents and conducting survey after survey on employment and wages, household demographics, and educational levels. He made sure to pay a visit to Dorsey; Du Bois acknowledged in The Philadelphia Negro his use of Dorsey’s scrapbooks.

Today, other writers and scholars recognize the profound importance of materials such as the Dorsey collection—resources collected and preserved informally by African Americans at a time when white historians claimed that African Americans had no history to speak of. These historians also had little interest in the lives of ordinary people. Though the Dorsey scrapbooks have endured, their preservation and accessibility to scholars who can interpret them are not guaranteed. The small, historically Black institution that owns the scrapbooks has lacked the resources to best house or maintain them. And a partnership between that institution and the predominantly white one that today physically stores the Dorsey collection has never been expanded to ensure needed conservation.

William Henry Dorsey was the son of Thomas Dorsey, an enslaved man who fled bondage in Maryland and, upon securing freedom, became one of Philadelphia’s leading caterers. He and his peers in the profession fed elite Philadelphians sumptuous feasts of lobster salad, deviled crab, and terrapin. In The Philadelphia Negro, W. E. B. Du Bois remarked that the elder Dorsey had “little education but great refinement of manner,” which he parlayed into relationships with the abolitionist and editor William Lloyd Garrison and the various politicians who graced his table. In his home museum, William Henry Dorsey would prominently display a letter that the antislavery senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts had written to his father.

Thomas Dorsey died a wealthy man. The young Dorsey had what his father didn’t: the freedom and leisure to learn, and an inheritance. He attended the Institute for Colored Youth, a school founded by Quakers in Philadelphia. The school later moved outside the city and became Cheyney University. When he left the institute, Dorsey worked as a waiter and as a messenger for local government; he also occupied himself artistically as a painter, though with little success.

Dorsey was no lone-wolf archivist. His activities placed him among a race-minded group of Black Philadelphian bibliophiles, almost all of them inveterate collectors and many of them scrapbookers. In the autumn of 1897, Dorsey attended meetings with Black neighbors and artists, including the writer and suffragette Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, to found the American Negro Historical Society. A network of activist, autodidactic Black archivists created what the historian Laura Helton calls a “quiet infrastructure of black thought,” where indexers, list makers, and taxonomists organized data about Black lives and history. Ellen Gruber Garvey, who viewed some of Dorsey’s scrapbooks for her 2013 book, Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks From the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance, discerned a “language of juxtaposition” by which scrapbookers silently but powerfully reframed a narrative, sometimes choosing, for instance, to paste racist, white-authored articles in close proximity to clippings about the same subject that emphasized Black acumen and accomplishment. The result was a counternarrative and critique of the racist white press.

Dorsey didn’t confine his labors to archival work. He put his weight behind an effort to erect a monument to Octavius Catto, a Black educator and civil-rights leader murdered by an Irish immigrant in Philadelphia during Election Day violence in 1871—a tragic episode memorialized in one of Dorsey’s scrapbooks.

Reginald Pitts is a Pennsylvania-based scholar and genealogist whose research has helped flesh out the life of Harriet E. Wilson. (Wilson’s 1859 book, Our Nig, is widely considered the first novel published by a Black woman in the United States.) Pitts has also been documenting the work of the Black scrapbooker Joseph Cathcart. Other Black scrapbookers in Philadelphia included John Wesley Cromwell, William Carl “Uncle Billy” Bolivar, and Robert Adger. About 40 Cromwell scrapbooks (some made with Cathcart) are preserved in Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, but Bolivar’s and Adger’s have been lost. Bolivar’s book collection, only part of which has survived, was so large and inspired such pride that in 1914 his friends and relatives printed 250 copies of a 32-page brochure cataloging its contents—more than 800 works, including “Americana, Negroana, Manuscripts, Autograph Letters, Lincolniana, Rare Pamphlets.” Thinking of the glorious fullness of the libraries Bolivar and his contemporaries assembled, Pitts told me that if they had survived intact, “this would have been nirvana.”

The Philadelphians’ reach extended beyond their city’s wards and libraries into a national network of Black readers and collectors. These bibliophages set about constructing a history of Black America, well before the anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits published his 1941 book, The Myth of the Negro Past, which categorically refuted the historylessness that white scholars once attributed to Black Americans and people of African descent. This stitching together of traces and texts asserted that Black experiences and cultural products demanded scholarly inquiry, a belief that would be needed to counter white “Lost Cause” proponents and their invented ideology of happy slaves, Black rapists, and an incompetent interracial Reconstruction leadership after the Civil War. The books these collectors amassed—and created—became the literal and symbolic foundations of important library collections on African American history. Bolivar shopped for books with Arturo Schomburg, the Afro–Puerto Rican historian whose personal library seeded the institution now bearing his name, the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Sometime after Dorsey’s death, his scrapbooks were donated to Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater. The gift to Cheyney may have been made by Dorsey’s son, who periodically nursed his aging father. As Garvey speculates, “Maybe after you’ve been living with your father, who’s obsessed with his scrapbooks, you were sick of them.” She told me, more seriously, that members of the next generation might have been ambivalent about elements of the history Dorsey compiled, including slavery and lynching. Their attitude may have been, as she described it, “It’s not progress. It’s that terrible history. We don’t want to see it.” The motivation could also have been mundane—a simple case of posthumous housecleaning—or far-sighted: The family recognized the significance of the scrapbooks and sought a safe place for them.

Whatever the explanation, Dorsey’s capacious vision is both the collection’s beauty and its archival Achilles’ heel. Those hundreds of scrapbooks take up a lot of space, and necessitate a lot of time and expense to preserve them.

Precisely how the dorsey scrapbooks got to Cheyney remains the subject of many a (probably apocryphal) tale: accounts had them being stashed in a Dorsey family garage for a while, or in other less-than-ideal repositories; and rescued by a heroic Cheyney janitor who was cleaning out a storage room in the 1970s. The late historian Ira Berlin commented, in a 1991 review of Roger Lane’s William Dorsey’s Philadelphia & Ours, that “after years of neglect and inattention,” the collection had been recently rediscovered “among the effects of former Cheyney President Leslie Pinckney Hill.” Piecemeal grants made possible the microfilming of some of the scrapbooks, mostly biographical ones with notable subjects; more than 100 remain unfilmed. When Cheyney hired its first archivist, Eric Dulin, in 1996, the “archive” was a storage room crammed with museum-worthy artworks. Old documents and photographs were “all over the floor,” he told The Philadelphia Inquirer three years after taking the job. Compelling finds lurked amid the mess: pictures of an elderly W. E. B. Du Bois delivering an address on campus in 1949; letters from Booker T. Washington detailing his book donations to the school and inquiring about getting his son admitted there.

Cheyney’s current archivist, Keith Bingham, now 72, succeeded Dulin in 2007, and has since been the keeper of the Dorsey scrapbooks, much as Dorsey was “custodian” of the American Negro History Society. In 2013, Cheyney came to an agreement with Pennsylvania State University that sent the 388 Dorsey volumes off campus, to an institution almost three hours away, where the volumes could be assessed.

The collection has not returned to Cheyney since its departure. Fluctuating temperatures and humidity are the enemies of paper, and Cheyney has no place that is sufficiently climate-controlled, including the library itself. The condition of the scrapbooks varies. According to Jennifer Meehan, the director of the Eberly Family Special Collections Library at Penn State, which holds the scrapbooks, a 2013 report on the state of the volumes found them to be in “fair to poor condition. Some of the condition issues identified are: mold and water damage; damaged and/or missing bindings; brittle pages; acidic, brittle and folded clippings.” Opening some scrapbooks would be difficult, and scanning to digitize isn’t always an option.

Yet repairs that would slow deterioration have not been undertaken, and there’s no financial estimate of what it would require to tackle the mammoth task of conserving all of the scrapbooks. The Cheyney–Penn State agreement stipulated only that Cheyney would lend the materials for 150 days as part of an archiving project. No other agreement has been signed, despite multiple attempts to execute one. Penn State continues to act as temporary guardian. Cheyney is the gatekeeper. No one can see the originals at Penn State without Bingham’s consent. Before Cheyney’s Hill Library closed this summer, researchers could at least consult microfilm of 260 scrapbooks (funding ran out before the remaining 128 could be committed to reels).

Archival work may be a low priority at an institution that has been struggling to stay afloat. Cheyney has laid off staff, eliminated its football team, and made technological and other infrastructure improvements in order to remain open. Presidents have come and gone. Enrollment has suffered: The university had 600 students in 2020, a big drop from more than 1,400 in 2008. With a $10 million shortfall in early 2019 and the threat of accreditation loss, the university launched both an austerity plan and an emergency fundraising campaign that netted more than $4 million. (Cheyney retained its accreditation.)

The new funds may not be enough. Bingham is scheduled to be “retrenched”—essentially, laid off—when the semester ends in May. His office was moved to a computer lab. Students can “ask a librarian,” but there are only two staffers now.

A representative for the public-relations company that handles Cheyney’s communications sent a statement saying that the “transition may have an impact on [library] staffing … Additionally, the administration is currently developing a long-term plan to ensure the safety and security of all University-owned materials and archived documents. This plan includes creating an environment to properly store archived documents that are currently located offsite in climate-controlled facilities. We will continue to protect our invaluable archived collections for the entire Cheyney community and to allow access for anyone interested in learning about the important events and people that have made and shaped Cheyney over the past 184 years.”

To make his scrapbooks, Dorsey often pasted images, handbills, and tickets onto printed pages. (Courtesy of the Penn Libraries)

The question of what will happen to the Dorsey scrapbooks is part of a larger question about the archival patrimony of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Some schools struggle with the poor funding that has distinguished them as separate and unequal from the beginning—which for many was in the 1890s, after a federal land grant set aside money for their creation as public institutions. But as the community institutions most responsible for the higher education of Black Americans after emancipation, they embody a sizable chunk of American, African American, educational, and religious history. Inside their archives—even those small archives that specialize in documenting their own institution—are multitudes of stories. And partnering with bigger, powerful, and better-resourced predominantly white institutions comes with a fear of losing de facto control of precious Black cultural resources—seeing the Dorsey scrapbooks, say, become a documentary equivalent of the Elgin marbles.

Ida Jones, a historian and the university archivist at Morgan State University, in Maryland, takes issue with the blanket notion that HBCU archives are in crisis. She prefers to say that there are “concerns.” She avoids the “crisis” label, she told me, in part because it is too often used as a way to blame the institutions themselves, and because it draws attention away from the historical and ongoing underfunding of Black institutions. “When you talk about an archive or a library,” Jones said, “we can’t save her neck because we like the necklace. We have to save the whole body.”

She also pointed out that HBCUs are not homogenous. They include private schools and public entities, those established as land-grant institutions and others created by missionary societies. Some are just staying afloat and others are enjoying growth spurts and in robust health. Some were started by educational entrepreneurs like Mary McLeod Bethune, who built Florida’s Bethune-Cookman University through skillful cultivation of high-dollar white patrons, donations from Black churches and communities, sweet-potato-pie sales, and sheer force of will. Some HBCU archives have prospered because they had high-profile librarian-ambassadors, such as Howard University’s late Dorothy Porter Wesley, who curated and amassed much of the Moorland-Spingarn’s globally recognized holdings.

What some people see as an HBCU problem tends to be a small-institution problem, says Lopez Matthews, a librarian who manages Howard University’s digital production center. Many HBCUs and small, predominantly white colleges don’t have archivists at all. Lincoln University, the other HBCU in Pennsylvania, is like many that get by with librarians who do double or triple duty, overseeing special collections and shouldering other responsibilities. Archivists like Bingham are sometimes called lone arrangers—they assist researchers, they inventory collections, they help students with term papers, they juggle front-desk duties, and sometimes they teach classes. Spelman College, in Georgia, has what its archivist Holly Smith calls a “small and mighty team of two.”

Crystal deGregory, an HBCU historian and a research scholar at Middle Tennessee State University, understands that every institution is different and that analytical nuance is needed when assessing its circumstances. But when I asked whether the future of any specific HBCU archive gives her cause for worry, she replied, “Every single one of them.” DeGregory described HBCU archives as both “magical and mortal.” Magical because of the way they’ve transformed what Du Bois once called “a small nation of people”; mortal because of how vulnerable small ones can be to overly hierarchical leadership and larger structural problems.

She noted the insidious trickle-down effects of underfunding: HBCUs’ hiring a faculty historian and archivist all rolled into one, stretching an individual beyond what any individual can do. Without staff, procuring grants that can support necessary projects is difficult. Many schools lack staff to process the collections already in their holdings. Even so, no one argues that wealthier institutions should have carte blanche to buy, claim, or obtain control of Black archival materials. Matthews, at Howard, told me that the notion of an overarching HBCU crisis “is a bit dramatic. Yes, we are understaffed. But I think that with support we can take care of our collection.”

Howard, a much bigger HBCU than Cheyney, fruitfully partnered with Penn State to digitize records of the educator and feminist Anna Julia Cooper. It was a win-win. “They hired a Howard student, she digitized the records, and they’re up,” Matthews said. “People are using them, and this student got to learn valuable skills. We came together as equals with a shared goal. That’s not the case with all partnerships. We always ask if we will benefit from them. It’s easier to say that with a smaller, focused partnership … But we don’t need to give our resources to other people to tell our history.”

As for the Dorsey scrapbooks, we know at least that they are being stored in acid-free boxes away from heat, light, and moisture. Without stabilization and conservation, easily available microfilm copies, or an agreement about their upkeep, they will be accessible in theory, but in practice beyond reach. The Dorsey collection remains at once lost and found—and in limbo.

Cynthia R. Greenlee is a historian, editor, and writer based in North Carolina. She’s co-editor of the forthcoming anthology, “The Echoing Ida Collection,” of black women and nonbinary writers on reproductive and social justice. She’s also the winner of a 2020 James Beard Foundation Award for excellence in food writing.

Cynthia R. Greenlee is a historian, editor, and writer based in North Carolina. She’s co-editor of the forthcoming anthology, “The Echoing Ida Collection,” of black women and nonbinary writers on reproductive and social justice. She’s also the winner of a 2020 James Beard Foundation Award for excellence in food writing.

There are no comments

Add yours