When I was in second grade, Disney released “Pocahontas.” As a small child, I was ecstatic, and relieved, to see an Indian princess in a Disney movie. I knew I was from the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. I loved watching Ariel in the “Little Mermaid,” but I knew I didn’t look like her. I watched Belle in “Beauty and the Beast,” but I didn’t look like her. They weren’t Indian. My mama bought me “Pocahontas” the day it was released on VHS. I vividly remember sitting too close to the television screen on that Friday night in complete anticipation. Even as a child, I recognized that representation mattered.

Too soon, however, I began to question this representation. “Well, she is Indian but I still don’t look like her. I don’t dress like her. I don’t talk like her. There are no cliffs around me. I don’t talk to trees or animals. I’m not like her at all!” Before I knew it, Disney Pocahontas became my least favorite Disney princess movie. I was completely disappointed and frustrated. One day I learned the real story of Pocahontas: she was kidnapped, raped, tormented. I was astounded to learn this because it is complete opposite of Disney’s portrayal of her. The story of Pocahontas is not child friendly yet Disney, and society, paints her as an amicable bridge between White settlers and Indigenous people, as a betrayer of her own Powhatan people. I believe that too often a false narrative is easier to absorb than the brutal and cold truths, especially in American history.

Individuals tend to use teepees, headdresses, dreamcatchers, buckskin, and drums to represent Indigenous people. While these are significant in many Native tribes and communities, Indigenous people are not monolithic. Tribes have different customs, traditions, values, and beliefs. Moreover, many times these aspects of Indigenous identity are highly romanticized and represented as caricatures that depict Indigenous people as historical figures.

Recently, my three-year-old daughter came home with a coloring sheet of a teepee. I asked her, “Can you tell me what this is?” She responded, “A teepee.” I simply replied, “Yes, this is a picture of a teepee. Some Native American tribes did at one time live in teepees but our Lumbee people did not.” Of course, she simply stated, “Okay.” Indigenous people are not merely primitive people of the past who do not exist today. We are writers, doctors, lawyers, educators, musicians, artists, farmers, entrepreneurs, scientists, construction workers, industrialists, politicians. We lead, think, create, serve, read, and teach. We are alive and thriving.

While schools, companies, organizations, and other venues may decide to celebrate Indigenous people in November, the celebration is often dehumanizing, immoral, and impudent. The effects of this is that negative stereotypes of Indigenous people are perpetuated. For example, one time a high school classmate said to me, “Why can’t you people just be American? Why do y’all have to talk to the sun or worship the sun? Why can’t you just be normal?” While it was not my responsibility to educate my fellow classmate, I felt it was a moral obligation to correct him. Unfortunately, I feel this same obligation today.

It is tiresome to constantly educate people on subject matters they should know. I should not have to tell someone why watching Disney Pocahontas is not appropriate for Native American Heritage Month or why allowing children to wear construction paper headdresses with Dollar Tree feathers is not fine. However, it is equally heartbreaking to think that my daughter will one day have similar experiences. While I acknowledge the lack of knowledge of Indigenous people due to limited education and years of perpetuated stereotypes, Indigenous people can no longer suffer due to the inept attempts, or lack of attempts, of people to unlearn inaccurate histories and seek the truth about Indigenous people.

I dread Native American Heritage Month because I’m constantly afraid my daughter will come home with an Indian headdress craft, coloring sheets of Native Americans and pilgrims enjoying a harmonious feast, or a teepee made of popsicle sticks and construction paper. The danger in this distorted perception of Indigenous people is that it creates a false sense of identity rooted in lies and inaccuracies, not an unwavering identity entrenched in truth, power, and pride. I remember countless nights flipping through books hoping to understand who I am as an Indigenous woman because my identity was never visible in textbooks, movies, or novels. I remember feeling both excitement and dread in November because while I relished in the acknowledgement of Indigenous people, there was immense trepidation in knowing the inaccuracies I would witness. I have battled this personally for years, but as a mother, I am compelled to think of the effects on my daughter. Like most parents, I try to protect my daughter from the perils of the world. However, Indigenous mothers have the added burden of protecting their daughters and sons from a society created to eradicate them.

I dread Native American Heritage Month because I’m constantly afraid my daughter will come home with an Indian headdress craft, coloring sheets of Native Americans and pilgrims enjoying a harmonious feast, or a teepee made of popsicle sticks and construction paper. The danger in this distorted perception of Indigenous people is that it creates a false sense of identity rooted in lies and inaccuracies, not an unwavering identity entrenched in truth, power, and pride. I remember countless nights flipping through books hoping to understand who I am as an Indigenous woman because my identity was never visible in textbooks, movies, or novels. I remember feeling both excitement and dread in November because while I relished in the acknowledgement of Indigenous people, there was immense trepidation in knowing the inaccuracies I would witness. I have battled this personally for years, but as a mother, I am compelled to think of the effects on my daughter. Like most parents, I try to protect my daughter from the perils of the world. However, Indigenous mothers have the added burden of protecting their daughters and sons from a society created to eradicate them.

What a privilege it must be to not worry how your child will be represented in textbooks, in television and movies, or in children’s books. What a privilege it must be to not fret how this will harm your child’s identity. I long for the day I am no longer afraid how the world perceives Indigenous people. My only hope is that my daughter, my future children, will not have to long for this day.

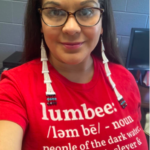

Concetta Bullard is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. She is a mother, wife, higher education professional, doctoral student, and a Follower of Jesus.

Concetta Bullard is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. She is a mother, wife, higher education professional, doctoral student, and a Follower of Jesus.

There are no comments

Add yours