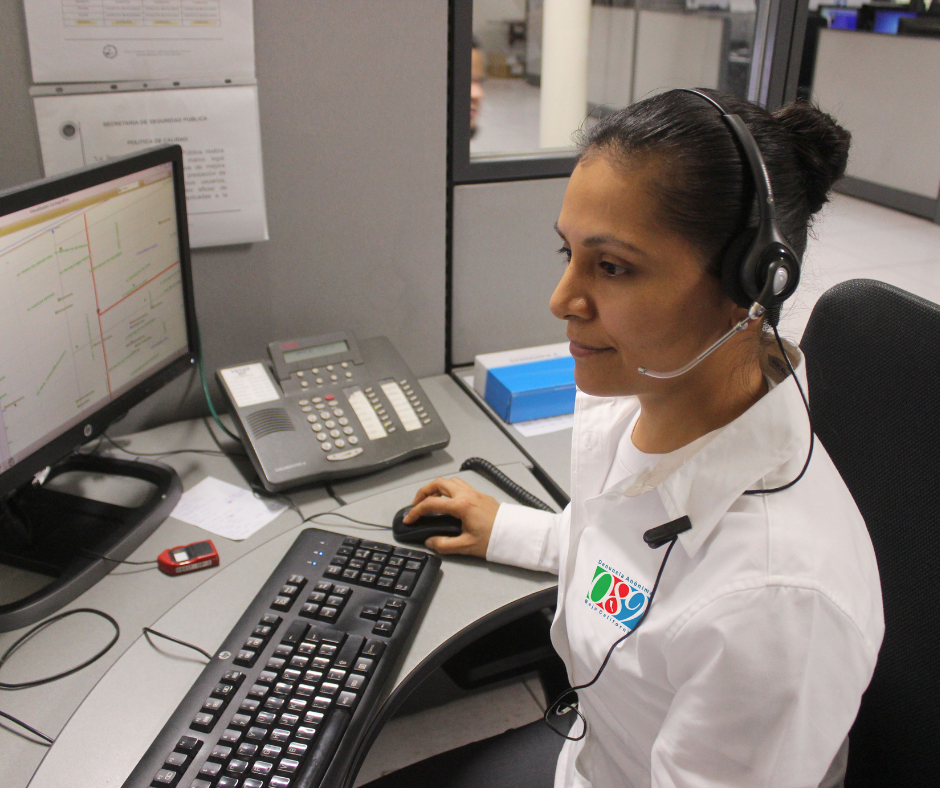

In the United States, there are approximately 98,000 public safety communicators. Also identified as first responders, they’re the people on the receiving end of 911 and non-emergency calls into communication centers. Deemed essential workers by the U.S.’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, these trained professionals have been inundated with an increase in calls during the global pandemic known as COVID-19. Despite this fact, the industry hasn’t been exempt from the decimation of jobs that has ravaged America’s economy.

In the United States, there are approximately 98,000 public safety communicators. Also identified as first responders, they’re the people on the receiving end of 911 and non-emergency calls into communication centers. Deemed essential workers by the U.S.’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, these trained professionals have been inundated with an increase in calls during the global pandemic known as COVID-19. Despite this fact, the industry hasn’t been exempt from the decimation of jobs that has ravaged America’s economy.

“Chadley” is experiencing the effects firsthand. A single mother of four, she was laid off in March from her part-time job as a 911 Telecommunicator, after serving for five years. Remembering what happened, the first responder recalls going to work on a Friday. By the following Tuesday, she was no longer employed.

“We were laid off to prevent the spread of the virus,” is what she was told. “We all work so close together. Anytime someone would get sick, they would encourage you to call out because you’re going to spread the germs. They wanted to reduce traffic into the center so only the full-time people were there. I think it was a preventative measure.”

While she understands their reasoning, the decision was unexpected.

“It was a shock,” Chadley confessed. “Typically, because we’re in such proximity, anything that’s discussed, we all know about it. As far as I knew, this wasn’t even being discussed.”

Despite the layoff, she never expected to be out of work for an extended period. Believing it would take possibly a month, at the most, to get the country back to “normal,” Chadley opted to not file for unemployment benefits … initially.

When what she envisioned began to give way to reality, she filled out the necessary forms to receive assistance. A couple of weeks later, Chadley received a letter in the mail informing her that due to the amount she had earned previously, her weekly benefits would total a whopping $44. Stunned but not deterred, she began to reflect on the circumstances that led her to this point. Circumstances that are rooted in the need for an increase in paid family and maternity leave in the United States.

When Chadley gave birth to her daughter in November 2018, she was employed full-time as a 911 Telecommunicator. She had health benefits, paid leave, and vacation time. If she worked over forty hours a week, it would accumulate as comp time, which translated into her earning a vacation day every two weeks. This worked well considering her family structure.

“It made things easier if the kids were sick because I knew I had days,” she said. “I knew that if I was sick, I had days. If you don’t have enough sick or vacation time, you have to come to work. Period.”

Chadley was granted 12 weeks for maternity leave. Her employer paid for half of those weeks. She used her sick and vacation time for the additional six weeks. According to North Carolina’s Paid Family Lave guidelines, she may have been eligible for an extra two weeks of pay. At the end of the three months, she wasn’t fully healed from her caesarean section and needed more time away from the job to care for herself. However, it wasn’t available.

Due to federal policy because she had been out of work 12 weeks, she was ineligible to seek additional time off under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Her supervisor agreed to allow her to take another two weeks off without pay.

“That sucked,” Chadley lamented. “Once you take FMLA or sick leave, you’re only getting a portion of your check. It was hard. At the end of the day, I was still having to pay this bill or decide what’s more important. What can I pay this time that I don’t have to pay next time so that I can pay the one I didn’t pay this time. It was the struggle bus. Maternity leave in this country is probably one of the worst systems we have.”

Returning to work was also a struggle. The mother of four noticed she was being treated differently. She was breastfeeding and had to adjust her pumping schedule. A week after her return, she was summoned to her supervisor’s office where he delivered unexpected news. Citing a previous oversight that had occurred months beforehand, he told her, “You should go part time before anything happens and I have to fire you.”

And she did.

“I wasn’t going to quit because I needed my job so I could pay my bills,” Chadley explained. “I’ve been forced to go back to school because I’ve lost all my benefits – my FMLA, vacation, sick. I was working five hours maybe once a week. It was better than nothing if that makes sense.”

It was a hard pill for her to swallow.

“Maternity leave definitely needs to be restructured. I feel like they could’ve given me more time to adjust my life – my milk supply, my time away from her. I didn’t feel supported when I came back. Nobody checked on me to see how I was doing. I had all of this on me and I’m trying to go to work and save other people’s lives. You have to leave everything else outside and it’s hard. You shouldn’t have to take out loans to live, especially when you have a full-time government job that could’ve been there for you.”

Now the job Chadley was leaning on to support her and her family as she finishes up her master’s degree in criminal justice is a thing of the past.

“I do miss my job,” Chadley admits. “I’m anxious but I’m not stressing. It’s a hard thing to go from I have an important job; I’m an essential worker. I save lives to nothing. I’m just at home teaching my kiddos, doing my own schooling, which I know isn’t a small feat. But it was part of who I was and now it’s not there anymore.”

Kassaundra Shanette Lockhart is a freelance writer.

There are no comments

Add yours