I don’t have teacher’s pets, but if I did, this year it might have been a young man named Alejandro. He was consistently late to my afternoon writing class because his family operated a food truck that catered to construction sites, and he needed to stay late every day to help them clean up.

I don’t have teacher’s pets, but if I did, this year it might have been a young man named Alejandro. He was consistently late to my afternoon writing class because his family operated a food truck that catered to construction sites, and he needed to stay late every day to help them clean up.

“You’ve never had a gordita?” he said early in the semester. “I’ll bring you one, Professor. It’ll be the best gordita you’ll ever taste.”

Alejandro had slick, black hair and a quick smile. He’s the only man I’ve ever known who could wear red leather shoes and get away with it. Every day, he was cheerful despite his multiple problems—his flat tire, his mother’s car wreck, his inability to find a parking place, and, of course, the constant tardiness—and always greeted me with an exuberant, “Hello, Professor!” On Valentine’s Day, he brought me a Big Kat Kit Kat bar.

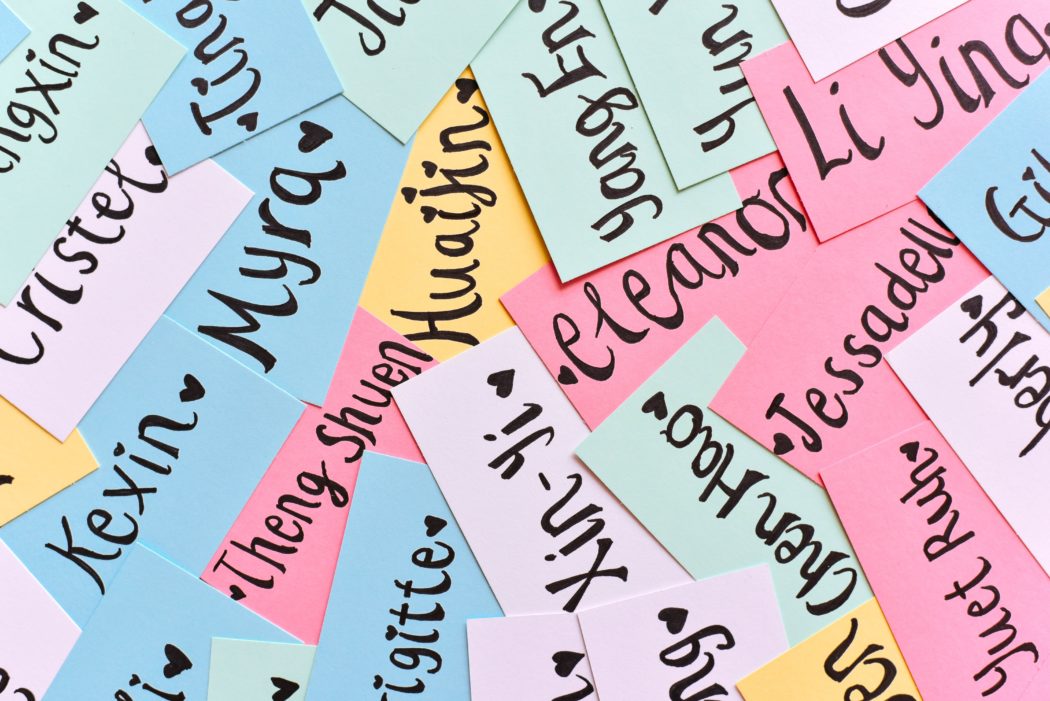

In that same class was Bhargav, Ysamuel, Hakmit, Laurenz, Geovany, Tjeteja, Lai, Jenna Aguilar, and Jimmy Romero. I teach at a university. I don’t teach international sections. These are my American students, all of them. American high school graduates with American life experiences. They eat, in addition to gorditas, lots of Chick-Fil-A and Bojangles. Their laptops are covered with stickers. They can’t stay off their phones. They love social media. They don’t sleep enough. They work too hard, balancing family, school, and jobs.

It’s been 40 years since I stepped into my first classroom at a small private college in eastern North Carolina. I don’t remember those students’ names, but what I remember was how much they looked alike and how similar their backgrounds were. They were good kids, nice kids, a bit lazier than the ones I’m seeing today, a bit less stressed, a bit more privileged. Of course, part of that difference is my shift from a small college to a large university, but that’s not the only, and not the main, difference.

Out of curiosity, I searched through old folders to find class rolls I had kept from my university teaching. The furthest back I could go was 2006, just 13 years ago. I checked the names: as I suspected, they were Katie, Sarah, Michael, Samantha, Jenny, Elizabeth, Brian, and Doug. Yes, there was one student named Phi and one named Tsay (pronounced “Way,” according to my scribbled in phonetic notes), but most of the rest were the old fashioned, traditional European names you might expect in a class from the 1960’s, the same names I grew up with, though by 2006, I had begun to see in my classes a healthy sprinkling of students with non-European names like Sahara and Asia, Kaneesha and Jaquan.

Names mean everything; names mean nothing. We are who we are, no matter what you call us. Yet our identity is tied up in our names; our culture or our age or our gender preference is sometimes reflected in our names. We grow into the names we were given or the names we have chosen to give ourselves.

What do I learn by comparing class lists of 13 years ago, of 40 years ago, to those today? Nothing I don’t already know. Nothing we all don’t already know: we live in a country of diversity. One American looks, sounds, eats, lives, worships differently from another American.

Something else I know but my class lists confirm: things have changed. My classrooms have changed. From the predominantly white classes of years back to the multicolored, multi-lingualed classes of today, students have changed.

I shudder when I confront those who believe in a white-only America, but those individuals are out there. If only they’d stick their heads into a classroom—from kindergarten to graduate school—they’d see what I see: classrooms rich with diversity, with culture, with interesting names, classrooms lively with discussion. This is our future. This is our now.

I never got my gordita, but that’s okay. What I got instead was the opportunity to get to know a pretty neat young man, different from me, and what a pleasure that has been.

Barbara Presnell is a writer and teacher of writing who loves to hear the stories her students tell.

There are no comments

Add yours