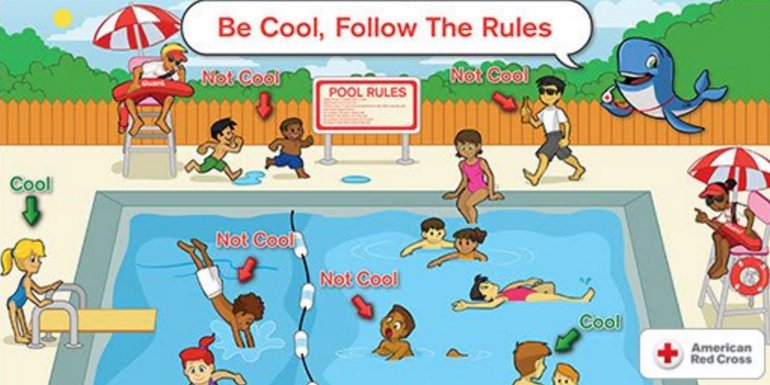

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the >>controversial Red Cross pool safety poster making its rounds on social media says a whole lot about where we are as a country when it comes to racism.

The poster has since been yanked by the nonprofit, but if you haven’t seen it, it features children of color doing “unsafe” activities: pushing, running, diving and even drowning themselves, with huge red arrows pointing to their faces saying “not cool.” The white children are totally “cool”. It’s enough to spark a heated debate.

How could a safety campaign by a well-established, national nonprofit that “shelters, feeds and provides emotional support to victims of disasters; supplies about 40% of the nation’s blood; teaches skills that save lives; provides international humanitarian aid; and supports military members and their families” create something so racially insensitive?

Let’s say “hi” to the elephant in the room: this picture is the tip of the iceberg, and you don’t have to dig deep in the icy water of our humanity to find out there’s so much more the image of “not cool” children of color illustrates.

Pool segregation lives on and so do the racist fears that fund it. Washington Monthly ’s Ed Kilgore said it with conviction: “Today, that complicated legacy persists across the United States. The public pools of mid-century—with their sandy beaches, manicured lawns, and well-tended facilities—are vanishingly rare. Those sorts of amenities are now generally found behind closed gates, funded by club fees or homeowners’ dues, and not by tax dollars.”

The lack of funding for public pools often leaves children of color out to dry. “Black children face a legacy of discrimination at public pools and beaches that makes them less likely to take up swimming as a recreational activity or sport,” said Ebony Rosemond, head of the Maryland-based organization called Black Kids Swim in an interview with The Washington Post . “Even now,” Rosemond said, “it’s often more difficult to find regulation-size pools for swimming and diving in black neighborhoods. Many other communities have turned to splash parks as a cheaper alternative to maintaining pools, which means many children never get a chance to truly swim.”

Growing up, I learned to swim at the place my community called the “Black Pool.” That wasn’t the official name, of course. “Washington Park” was built during the fight for school integration. Old newspapers reported that after years of the city refusing to build a pool in the neighborhood, this nod toward separate but equal “was intended to keep Negro children in their neighborhoods.”

Since my mother didn’t own a vehicle (and she was working during most summer days), my neighborhood friends walked down to the Black Pool back in the 1990’s. I thought things would have changed, until I returned home a decade later to see the disrepair of our community pool. I stood with my face pressed against the gates a few months ago as the Black Pool was torn down. After much debate, it too will become another splash pad.

Since the Red Cross poster has gone viral, many are coming forward to share their segregated pool stories. One friend shared that a grandmother refused to let children out of her car due to the ”strange” family at their neighborhood pool. He and his children were invited guests of a pool member.

But segregated pools aren’t the only problem.

Segregated nonprofits help to create these cultural competence gaps. Even those trying to “do good” don’t always get it. As a former nonprofit executive and board member for over a dozen charities (including my local Chapter of The American Red Cross), I can tell you that nonprofits aren’t always warm and fuzzy when it comes to authentic diversity in staffing or governance.

According to the Voice of Nonprofit Talent: Perceptions of Diversity in the Workplace , this gap leads to problems like the one of the pool poster. The lack of inclusiveness plays a sad but significant role in a general disconnect between nonprofits and the people they serve.

While I can’t speak as to the board or staff diversity of the American Red Cross, I can read between the lines of its blanket statement, “The American Red Cross appreciates and is sensitive to the concerns… We deeply apologize… it was absolutely not our intent to offend anyone… we are committed to diversity and inclusion… completing a formal agreement with a diversity advocacy organization… blah…blah…blah .”

I know that the Red Cross works diligently to serve families in need, but someone on the staff missed the historical and cultural significance of this issue. It’s great that there was pressure for this nonprofit to quickly issue an apology for the mishap — but that shouldn’t be the end of this discussion. We need to dig deeper — so racism, whether conscious or unconscious, doesn’t taint the waters of the next generation.

There are no comments

Add yours